It is estimated that more than a hundred children from Indigenous tribes in northern Brazil are killed each year because of traditions and cultural norms rooted in false beliefs. Thanks in large part to determined Christians, a new law in the works may prevent many of these deaths in the years to come.

“If they are born twins, if they have any kind of physical or mental disability, if they are born outside of wedlock, or born to single mothers, they might suffer a huge attack to one of their fundamental rights: their lives,” says Marcia Suzuki–a Brazilian who, along with her husband, Edson, are finally seeing meaningful fruit from their decade-long work to establish legislation protecting these children and many of their family members who want to save them.

According to Indigenous leaders, the children are killed for religious or spiritual reasons: Disabled children are thought to be cursed and thus harbingers of bad luck, a twin or triplet is suspected to be harboring an evil spirit and, in some tribes, the shaman has the power to decide that a child must be killed simply based on his “impressions” about the nature of that child.

Marcia and Edson are part of Youth with a Mission, a DNA affiliate organization. While enduring overt attacks from some anthropologists and government officials, Marcia says the book Discipling Nations confirmed that they were doing the right thing in fighting this lie that ensnares part of Brazil’s culture. “I felt very encouraged to keep following God’s dreams for my nation,” she says.

An invisible but deadly foe

It could be easy to point the finger at the parents of these murdered children, but Marcia has seen parents flee their tribes or even sacrifice their own lives to save their children.

The real enemy, she says, is invisible: it is the moral and cultural relativism that makes questioning the practice of infanticide taboo.

“I’m not going to defend infanticide,” said Fiona Watson of Survival International, a group that defends the right of native tribes all over the world, in a 2008 interview with USA Today. “But I think you have to understand,” she says, that in the context of Indian culture, “it’s not considered murder.

“In fact,” she said, “it’s often considered something which is a kind thing to do. If you have somebody who is born into your community who is not going to survive, who is very badly deformed and you are an Indigenous people who are living deep in the jungle, you don’t have access to medical care, that is the kindest thing to do.”

An anthropologist from the University of Brasilia agrees:

“An indigenous child, when he or she is born, is not a person. He or she will undergo a long personalization process until acquiring a name and, with that, the status of a ‘person.’ Therefore, the very rare cases of newborns who are not inserted in the community’s social life cannot be described as death, because that is what it is not. Infanticide, then, it is never.”

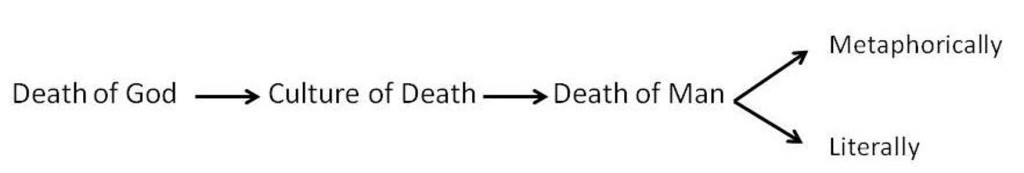

Marcia calls this “racism doctored up with political correctness and so-called cultural tolerance,” and it is the kind of relativism DNA co-founder Darrow Miller describes when he says “with the death of God, a culture of death is born” (read more).

Francis Schaeffer once said, “I believe that pluralistic secularism [relativism], in the long run, is a more deadly poison than straightforward persecution.”

Exposing the lies

On August 26, 2015, the Brazilian Congress approved a law that fights the infanticide in Indigenous areas. It is called Muwaji’s Law, named after an Indigenous mother who refused to bury alive her own baby. This is a significant victory, but the law still must pass the senate and be signed by Brazil’s president.

“This may be the biggest achievement in YWAM Brazil in the 40 years since its foundation,” says Ricardo Otake of University of the Nations in Hawaii. “This bill allows Indigenous people the access to go against their cultural practices in order to defend the lives of their own children.”

Marcia joined YWAM in 1980 and pioneered the organization’s ministry among Indigenous tribes in 1982. In 1990, she married Edson and joined his ministry among the Suruwaha tribe. Both are trained linguists and Bible translators whose story is told in this book.

“After living for over a decade with the tribes,” Marcia says, “we realized that certain children just disappeared and no one seemed to be willing to explain to us what had happened to those children. As we looked closer into the issue, we realized that the mothers were killing their own children and suffering terribly because of that.”

In the year 2000, Marcia and Edson assumed the care of a 5-year-old, 15-pound infanticide survivor, filing for her adoption and eventually becoming her legal parents. Their daughter, Hakani, was terribly abused and neglected by most of her tribe because she was unable to walk as a toddler, and the experience led the Suzukis to create a docudrama called Hakani. This short film got more than a million views on YouTube in 2008, and it also attracted hostility from the Brazilian government and anthropologists. Simultaneously, the film was seen by more than 80 Indigenous tribes, leading many leaders to put a stop to the tradition in their communities.

Two years before the release of Hakani, the Suzukis founded Atini, an organization that defends the rights of Indigenous children by raising awareness about infanticide, educating the tribes, and providing alternatives for families who wish not to kill their children.

Breaking the silence

“It is not difficult to change the tradition in the tribes because they love their children,” Marcia says. “Once the taboo is broken and the dialogue is open, the Indians usually are very open to alternatives like medical care, sending the children to adoption or raising them outside the tribe.”

“It is not difficult to find resonance with most of the Brazilian population,” she continues. “Eighty percent of Brazilians are against abortion, and they immediately understand that to protect life is more important than to protect culture.

“The problem is to change the official policy for Indigenous people. The policy is very influenced by moral and cultural relativism; there is a lot of pride and control involved. Also, there is a lot of interest in the Indigenous lands and in the Amazon in general, and the government many times uses the Indians as an excuse to keep people away from the isolated areas so they can do whatever they want there.”

To practically meet the needs of Indigenous families while maintaining presence in the sight of the government, Atini established a sanctuary in Brazil’s capital city–close to the congress, senate and all political powers.

Photos of Atini sanctuary by Lindsay Kennedy

Here, families pressured to kill their children come for help. They are given housing, education, the ability to grow crops and earn a living, and medical care especially for those children threatened due to a disability. This is a temporary home for up to 80 people at once with the goal of the families returning to their tribes once the child’s medical condition is resolved or when the tribe chooses to accept the child back. In cases when the child never is welcomed back, Atini helps the family establish a new life in a new community.

Truth prevails

Moroni Torgan (left), a congressman from the DEM party in the Brazilian state of Ceará, says life should be a fundamental value applied to every culture.

With the passage of this law, infanticide will be illegal even in an Indigenous tribe. The new legislation criminalizes tribe members who kill their children only when it is proven that they knew they were committing a crime under Brazilian law. Notably, the law requires every government worker or missionary to report children in risk to the authorities. Authorities then must provide alternatives for the child, such as medical care, counseling, temporary shelter outside the tribe, or adoption. In this way, people trying to protect children will themselves be protected from prosecution.

Following the Suzukis’ lead

It is remarkable that Marcia, Edson and their small team could influence a nation as large as Brazil at the legislative level. They give glory to God and encourage others not to shy away from challenging widespread cultural sins that may seem insurmountable.

“We started small, making small changes, influencing people around us first,” Marcia says. “We never thought we would influence the entire country or change the law in day. Brazil is a huge country: 200 million people and the seventh economy in the world. We were not aiming at that.

“But we started saving the lives of the children around us and fighting for the rights of the their families to keep them alive. We brought them to our own home first. We just felt we had to be faithful to the principles of justice and integrity.

“What we were doing was very simple and uncomplicated, but it challenged the powers in our country. When we realised that our simple actions of justice and love were creating such national debate in the country, then our eyes were opened to what God wanted to do through our lives. He gave us an amazing visibility, so our small action of love would touch a country and save hundreds and thousands of lives.”